Tax Preparation and the Earned Income Tax Credit in Rural America

Only about 80% of eligible individuals nationally claim the EITC, and folks living in rural areas are less likely to do so than those in urban areas. Given its importance to impoverished communities, the ncIMPACT Initiative at the UNC School of Government is working on a Rural EITC Uptake Project with Rural Forward NC, the UNC School of Social Work’s Jordan Institute for Families, and the NC Justice Center. This ongoing project is taking place in Beaufort, Edgecombe, Halifax, McDowell, Nash, Robeson, and Rockingham counties and is working to both understand the number of eligible individuals claiming the credit and reasons that the credit may go unclaimed.

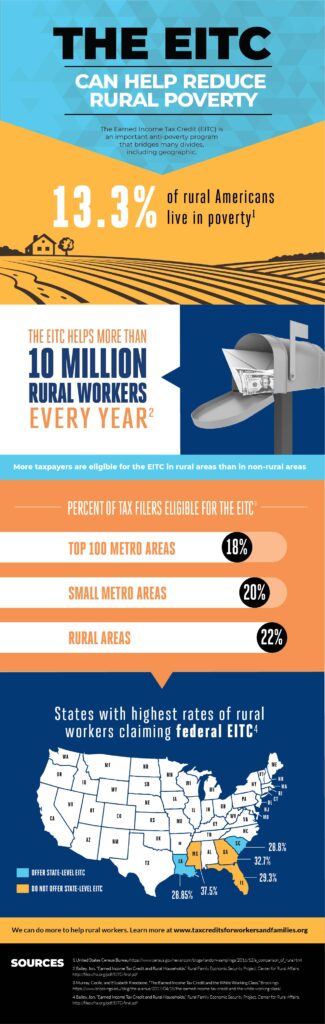

The 2020 COVID-19 pandemic has brought the economic conditions of low-income Americans to the forefront of media and government policy. Federal tax refund programs like the Earned Income Tax Credit offer opportunities for governments to positively impact those living in poverty. The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) is a refundable credit that working adults and families can receive each year, and is the federal government’s largest benefit for workers. It has enjoyed decades of bipartisan support and can often amount to thousands of dollars that both reduces a family’s tax burden (amount of taxes paid) and can serve as a source of tax-free income, if the credit is more than taxes owed. However, its amount differs depending on income, tax filing status (single, joint, etc.), and number of dependents. Those that receive the EITC often use it to pay down debt, make important purchases or repairs, or pay bills like rent or utilities.

Only about 80% of eligible individuals nationally claim the EITC, and folks living in rural areas are less likely to do so than those in urban areas. Given its importance to impoverished communities, the ncIMPACT Initiative at the UNC School of Government is working on a Rural EITC Uptake Project with Rural Forward NC, the UNC School of Social Work’s Jordan Institute for Families, and the NC Justice Center. This ongoing project is taking place in Beaufort, Edgecombe, Halifax, McDowell, Nash, Robeson, and Rockingham counties and is working to both understand the number of eligible individuals claiming the credit and reasons that the credit may go unclaimed.

Earlier this summer, community members who are participating as part of local research teams in each county raised an important question: why are rural tax preparers not connecting their clients with the EITC? This spurred research[1] into the state of tax preparation and its connection with the EITC in rural areas, which came to the following conclusions:

- Multiple barriers exist to filing taxes in rural areas.

- These barriers negatively impact EITC claims in rural areas.

- Low-income filers are more likely to use tax preparers and are more vulnerable to predatory tax preparers.

- There are strategies that can increase EITC claims and the positive financial impact of the credit for rural families.

Tax Filing Barriers

Individuals in rural areas are not just less likely to claim the EITC; they are less likely to file taxes in general. The barriers include: time and transportation; lack of preparers; limited English competency; lack of broadband access; and lack of knowledge about the tax system. There is not adequate EITC-knowledgeable, reputable tax preparer density in many low-income rural areas. This is particularly true for VITA and other free or low-cost tax preparation services.[2] This makes rural families more likely to have to travel a greater distance to find and use a tax preparer’s services.[3] This is compounded by lack of broadband access, which limits the availability of e-filing. E-filing reduces dependence on paid preparers, increases EITC participation, and increases with broadband access.[4] Finally, rural Americans may lack knowledge about the existence of the EITC, eligibility for the credit, and its potential positive impact on incomes. Some families may be choosing not to file taxes at all.[5] Additionally, families for whom English is not the first language who reside in rural areas must deal with all of these barriers, plus the added one of limited English competency.[6]

Impact on EITC Claims

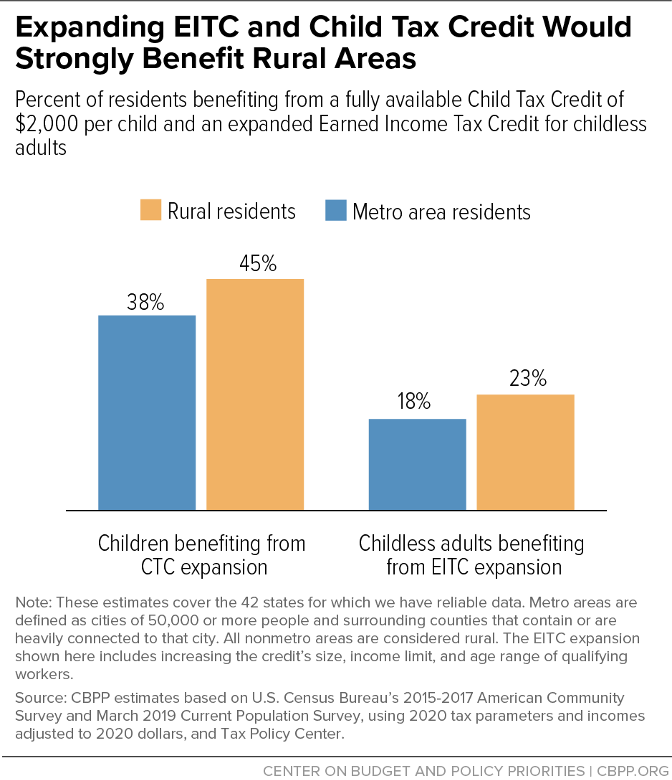

Many low-income families may lack the types of regular social contacts that would lead to awareness of the EITC and its benefits, and limited accessibility of free and low-cost tax preparation sites can seriously hinder EITC claims in rural areas because of transportation and accessibility concerns.[7] These barriers also create a lack of knowledge about the negative effects of the costs and fees associated with paid and predatory tax preparers. This limits families’ abilities to financially plan for the year, make necessary purchases, and build their savings and assets because of the associated reduction in the credit refund amount.[8]

The Role of Tax Preparers

Low-income filers are increasingly using paid tax preparers. Potential reasons for this trend include wanting to avoid interactions with the IRS; avoid noncompliance and its associated penalties; and because tax preparers are generally trusted – 91% of taxpayers trust that preparers have the required knowledge to help them file a return.[9] However, using paid tax preparers can come with a series of possible pitfalls, mostly due to the cost of tax preparation and the vulnerability of low-income folks to predatory preparers and alternative financial services (AFS). EITC returns are disproportionately filed by paid preparers – 62% of EITC claims in 1998, as opposed to 53% of all returns[10] – but the direct and indirect costs of paid preparers, like fees and increased filing time, “make up a larger percentage of income for low-income filers.”[11] Additionally, low-income individuals are more likely to use alternative financial services, like payday and title loans, pawn shops, and check cashing establishments, many of which have exorbitant fees associated with their services. This makes them more likely to come into contact with predatory tax preparers who charge more, have hidden fees, or use rapid refund loans (in which filers are given a loan amount in exchange for the preparer keeping any refund they receive from their return, which is often higher than the loan amount).[12]

Strategies to Increase Uptake

Despite these barriers, there are strategies available in the literature that can increase tax filing, EITC claims, and the positive financial impacts of EITC refunds for low-income families. These include:

- Creating multilingual outreach campaigns that focus on the financial benefits of the EITC to encourage uptake.[13]

- Connecting with family financial educators to target eligible individuals who are less likely to claim the EITC, and creating partnerships between EITC outreach campaigns and local family educators who have close contact with low-income families already. [14]

- Providing accessible free tax preparation services or resources needed to use them:

- Using financial planners at VITA sites or informing financial educators in the community about how to plan for the large, windfall-like nature of the EITC to assist families in better utilizing it for their financial priorities, including saving and asset building.[17]

- Getting EITC recipients into the formal financial system, including setting up bank accounts for refund direct deposit, to reduce their reliance on predatory Alternative Financial Services (AFS), like rapid refund loans, payday loans, and check cashing establishments, among others.[18]

ncIMPACT’s EITC project is designed to discover if these barriers and strategies are relevant in local North Carolina communities. As the project progresses, we hope that our partner institutions and community participants will help us identify successes, gaps, and solutions to increase EITC uptake in rural communities and provide a vital financial lifeline to families in poverty.

References

Fleischman, G. M., & Stephenson, T. (2012). Client Variables Associated With Four Key Determinants of Demand for Tax Preparer Services: An Exploratory Study. Accounting Horizons, 26(3), 417-437. Retrieved from http://libproxy.lib.unc.edu/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/docview/1095109550?accountid=14244.

Gudmunson, C.G., Son, S., Lee, J. & Bauer, J.W. (2010). EITC Participation and Association With Financial Distress Among Rural Low‐Income Families. Family Relations, 59: 369-382. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3729.2010.00609.x.

Gunter, S.R. (2019). Your Biggest Refund, Guaranteed? Internet Access, Tax Filing Method, and Reported Tax Liability. Int Tax Public Finance 26, 536–570. https://doi-org.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/10.1007/s10797-018-9528-x.

Hall, C. & Romich, L. (2016) “Low- and Moderate-Income Tax Filers Underestimate Tax Refunds: Implications for Financial Counseling and Policy.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 27(1): 36-46. DOI:http://dx.doi.org.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/10.1891/1052-3073.27.1.36.

Hirasuna, D. P., & Stinson, T. F. (2004). Do Free Tax Preparation Sites Increase Utilization Of State Earned Income Credits? Evidence From Minnesota. Washington: National Tax Association. Retrieved from http://libproxy.lib.unc.edu/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/docview/195448374?accountid=14244.

Leviner, S. (2012). The Role Tax Preparers Play in Taxpayer Compliance: An Empirical Investigation with Policy Implications. Buffalo Law Review 60(4), 1079-1138. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/buffalolawreview/vol60/iss4/4.

Lim, Y., Livermore, M., & Davis, B.C. (2011). Tax Filing and Other Financial Behaviors of EITC-Eligible Households: Differences of Banked and Unbanked. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 22(2): 16-27,75-76. http://libproxy.lib.unc.edu/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/docview/1018171327?accountid=14244.

Mammen, S., & Lawrence, F. (2006). How Rural Working Families Use the Earned Income Tax Credit: A Mixed Methods Analysis.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 17(1), 51-63. http://libproxy.lib.unc.edu/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/docview/1355866357?accountid=14244.

Mammen, S., Lawrence, F.C., & Marie, P.S., et al. (2011). The Earned Income Tax Credit and Rural Families: Differences between Non-Participants and Participants. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 32, 461–472. https://doi-org.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/10.1007/s10834-010-9238-8.

Pippin, S. E., & Tosun, M. S. (2014). Electronic Tax Filing in the United States: An Analysis of Possible Success Factors: EJEG EJEG. Electronic Journal of E-Government, 12(1), 22-38. Retrieved from http://libproxy.lib.unc.edu/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/docview/1640729890?accountid=14244.

Varcoe, K., Lees, N. & Lopez, M. (2004). Rural Latino Families in California are Missing Earned Income Tax Benefits. California Agriculture, 58(1):24-27 DOI: 10.3733/ca.v058n01.

[1] This literature review was completed by Lea Efird (ncIMPACT Initiative summer fellow), Rebecca Hall (Rural Forward NC summer associate), and Avery Walter (Rural Forward NC summer associate) in July 2020.

[2] Mammen, S., Lawrence, F.C., & Marie, P.S., et al. (2011).

[3] Ibid; Gudmunson, C.G., Son, S., Lee, J. & Bauer, J.W. (2010).

[4] Gunter, S.R. (2019); Pippin & Tosun, (2014).

[5] Mammen, S., & Lawrence, F. (2006); Mammen, S., Lawrence, F.C., & Marie, P.S., et al. (2011).

[6] Gudmunson, C.G., Son, S., Lee, J. & Bauer, J.W. (2010); Pippin, S. E., & Tosun, M. S. (2014); Varcoe, K., Lees, N. & Lopez, M. (2004).

[7] [7] Gudmunson, C.G., Son, S., Lee, J. & Bauer, J.W. (2010).

[8] Mammen & Lawrence, (2006); Hall & Romich, (2016).

[9] Hirasuna, D. P., & Stinson, T. F. (2004); Fleischman & Stephenson, (2012); Leviner, (2012).

[10] Gunter, S.R. (2019).

[11] Hirasuna, D. P., & Stinson, T. F. (2004)

[12] Lim, Livermore, & Davis, (2011).

[13] Mammen & Lawrence, (2006); Mammen, Lawrence, & Marie, et al., (2011); Varcoe, Lees, & Lopez, (2004).

[14] Gudmunsun et al., (2010).

[15] Mammen & Lawrence, (2006); Mammen, Lawrence, & Marie, et al., (2011).

[16] Gudmunsun et al., (2010).

[17] Hall & Romich, (2016).

[18] Lim, Livermore, & Davis, (2011).