Where are the Workers?

Coming off a busy holiday season, it’s probably clearer to many of us just how strained the American labor market is right now. Maybe you had to wait in a long line to check out while doing your Christmas shopping, or some of the ingredients for your Thanksgiving meal weren’t available on the shelf at the local grocery store. Maybe a friend wasn’t able to attend a holiday party due to a flight cancellation because of limited crew, or some packages were late to arrive on your doorstep. In each case, we can point to a tight labor market that’s yielded fewer workers where we need them, and disrupted the normal flow of goods and services to which we have become accustomed.

Co-Authored by Patrick Bradey

Over the holiday season, many consumers could be heard questioning, “Where are the workers?” The answer to this question matters for our daily needs and, more importantly, it is key to our nation’s economic recovery. The ncIMPACT Initiative at the UNC School of Government is spending a lot of time talking to experts to understand what can be done on a local or regional level to mitigate or stabilize this situation.

We recently had a chance to hear from two very different groups on their ideas for responses. First, we talked to leaders in local government, all designated as Local Government Federal Credit Union (LGFCU) Fellows by the UNC School of Government. Second, we heard from high school student leaders in the North Carolina Association of Student Councils (NCASC). We were surprised by the level of agreement between the two groups, and thought you might find insights in their common agreements and rare disagreements.

The Challenge

Before we get to that, however, it might help to share why this issue is so important.

There’s no question that the labor market has been in turmoil since the onset of COVID-19 in March 2020. Significant numbers of people lost or left their jobs as businesses and other organizations closed their doors or laid off staff as revenues fell. Many of these entities have now reopened or even expanded, but some still report that they are struggling to hire employees.

We know that employment and workforce issues are important not only in North Carolina, but across the country. Nationally, the labor force has shrunk by millions as people stay home for myriad reasons. Fear of a resurgent COVID strain, padded savings that allow people to take time off or search longer for a job, the construction of individualized income flows different from the traditional nine-to-five, and caregiving constraints that require more flexibility have all pulled people from the wider labor market as businesses seek to return to pre-COVID staffing and service levels.

This shortage of workers is a trend that has continued since the economic recovery began to kick into full swing. The effects may be seen far and wide – from help wanted signs in store windows, to popular media stories about the significant toll on workers in sectors such as healthcare, to data on business closures, as well as impacts on new business formations.

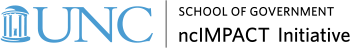

Indeed, data from the NC Department of Commerce indicates that the labor market is “tight” and fewer employees are applying for existing job openings.

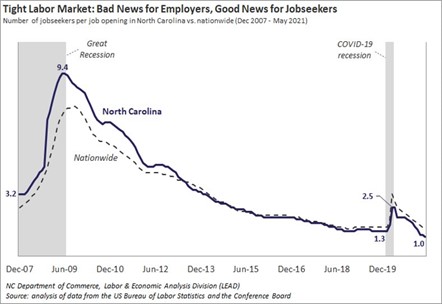

Quantitative and qualitative data from survey and interviews ncIMPACT Initiative recently coordinated for Carolina Across 100 reflect these trends, with respondents repeatedly expressing concerns about workforce shortages.

The Opportunity

ncIMPACT Initiative is serving as coordinator for Carolina Across 100, a five-year initiative for which the Chancellor of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill has charged the campus to partner with communities in each of the state’s 100 counties to help with recovery from the effects of the pandemic.The initiative’s first step was to hear from people across the state. Then, the Carolina Engagement Council (CEC) met on October 25 to consider what state residents shared in more than 3,200 usable (of 4,000) Carolina Across 100 survey responses and almost 100 interviews. They considered responses from people who live and/or work in every county of the state. Based on the priorities shared, the CEC decided that the focus for the first partnerships with communities had to be employment stability.

What Do LGFCU Fellows and NCASC Leaders Think?

We will make a public announcement about this program of work in early February 2022. Before then, we wanted to share what were heard from both LGFCU Fellows and high school student council leaders, based on what they see in their own communities.

- Work outside the home may not make economic sense for everyone. Some former workers, perhaps especially mothers of young children, may not return to the workforce anytime soon. Many have found that, with the rising cost of childcare, the lost income from having an adult stay home may be less than would be spent on childcare.

- Work must mean more than a paycheck. COVID has changed us all, even in ways we do not yet realize. People are trying to find more meaning in their lives. Employers who are able to offer flexibility and a sense of meaningful purpose will be more attractive to prospective employees.

- More people do not want to work a 9-5 job. These folks enjoy the independence and flexibility offered by positions that allow remote work or non-standard hours to accommodate personal preferences and other commitments outside of work. Many are willing to forego the security of traditional employment for the flexibility and independence of the gig economy.

- Pay does matter. As new opportunities have opened up, some who were working in lower-wage jobs now have relatively higher-wage options. Some of this is because of wage inflation and some of it is because there are workers who upskilled during the pandemic.

- Both the Fellows and high school student council representatives questioned whether federal unemployment payments have kept potential employees out of the labor force, making it harder for employers to recruit them. The two groups diverged on some key points, perhaps reflecting shifting perspectives on the world of work, including:

-

- Participants at the NCASC conference expressed that many people don’t see a lot of value in working a minimum wage job because the minimum wage may not be not a living wage, i.e. enough to meet the costs of the basic necessities of life. They were adamant that, increasingly, people in their generation expect employment opportunities that will pay basic bills, give a greater sense of fulfillment, and allow for time outside of work to spend on personal pursuits.

- On the other hand, the LGCFU Fellows were particularly attentive to hiring issues unique to local government. Public employment often involves additional processes and training that don’t allow local governments to stand up or scale up a workforce as quickly as some other sectors or employers might. They worried about keeping up with wage inflation, and the ability to offer the perks and flexibility that the private sector could offer.

So… Where Are Our Workers?

Coming off a busy holiday season, it’s probably clearer to many of us just how strained the American labor market is right now. Maybe you had to wait in a long line to check out while doing your Christmas shopping, or some of the ingredients for your Thanksgiving meal weren’t available on the shelf at the local grocery store. Maybe a friend wasn’t able to attend a holiday party due to a flight cancellation because of limited crew, or some packages were late to arrive on your doorstep.

In each case, we can point to a tight labor market that’s yielded fewer workers where we need them, and disrupted the normal flow of goods and services to which we have become accustomed. But we can’t say exactly where those workers have gone, to some extent because they are part of a great dispersal of labor.

As our LGFCU Fellows and NCASC leaders pointed out, many are pursuing other types of jobs that give them more flexibility, are otherwise occupied with taking care of aging loved ones or school-aged children who might be more vulnerable to COVID, or continuing to seek work outside of the sector where their labor had previously been focused.

And, tragically, many of them are dead. More than a quarter of COVID deaths in the United States to date have been of working-age people, a figure roughly equivalent to the entire population of Fayetteville, NC.

Some of the deceased were filling roles considered “essential” from the earliest days of the pandemic. These workers were on the front lines of making sure that the core social functions necessary to preserve life and health were maintained through our biggest crisis. It should be no wonder, then, that “essential” sectors are now those facing some of the greatest strain to fill their rosters.

The bigger question is how the labor market rebounds from its current state. Pay, flexibility, and meaningful work all came up as essential features of COVID-era job hunting in our conversation with the LCFCU Fellows, NCASC students, and our Carolina Across 100 survey respondents. To implement these features, along with continued mitigation efforts in the face of an ever-changing barrage of viral variants, will prove to be a truer test of the labor market’s adaptability than we’ve seen in a long time.