Water in North Carolina

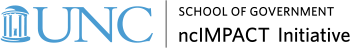

Our relationship with water varies with our circumstances. Communities often want more clean drinking water to catalyze economic development and serve new residents and businesses. At the same time, they want less polluted runoff and flooding from the growing number of rooftops and extreme weather events. As a warming climate generates more violent storms, flooding is damaging more lives and property. In many communities, the 100-year storm is becoming a regular occurrence.

The Challenge

Expensive infrastructure is needed to tap our water resources, maintain their quality and quantity, and help protect us from their harmful impacts during flooding. Aging facilities and rising construction prices are driving up costs. New treatment facilities take years to design and permit. Paying for facility construction and ongoing operation and maintenance is a continuing challenge. The State of North Carolina has established a strict framework for setting rates and fees for these services. Many communities are also subject to state and federal stormwater management requirements to help protect water quality in the face of increasing development impacts.

New challenges are presented by microplastics and per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), or so-called “forever chemicals” used in a variety of consumer products that are harmful to humans and don’t break down in the environment.

North Carolina is blessed with considerable water resources. Average annual rainfall ranges from about 50 inches a year on the coast to up to 80 inches a year in the mountains, well above the U.S. national average of 30 inches a year (Sources: Britannica; NOAA). At the same time, growth is straining this capacity and degrading water quality, with a number of streams no longer supporting their intended use, reducing opportunities for swimming and fishing, and increasing the cost of treatment for consumers.[1] To protect their water resources, communities need to work from the headwaters to the tap to maintain water quality and quantity. In turn, flooding and hurricanes cause more than $360 million in projected damage each year in North Carolina.[2] As a result, moving people and property out of harm’s way is an essential undertaking.

Potential Responses

Short-Term

- Create a calendar for coordinating and updating water supply plans and wastewater management plans with neighboring communities

- Create a water resources dashboard to track water quality, water supply, water conservation, watershed protection, and other topics

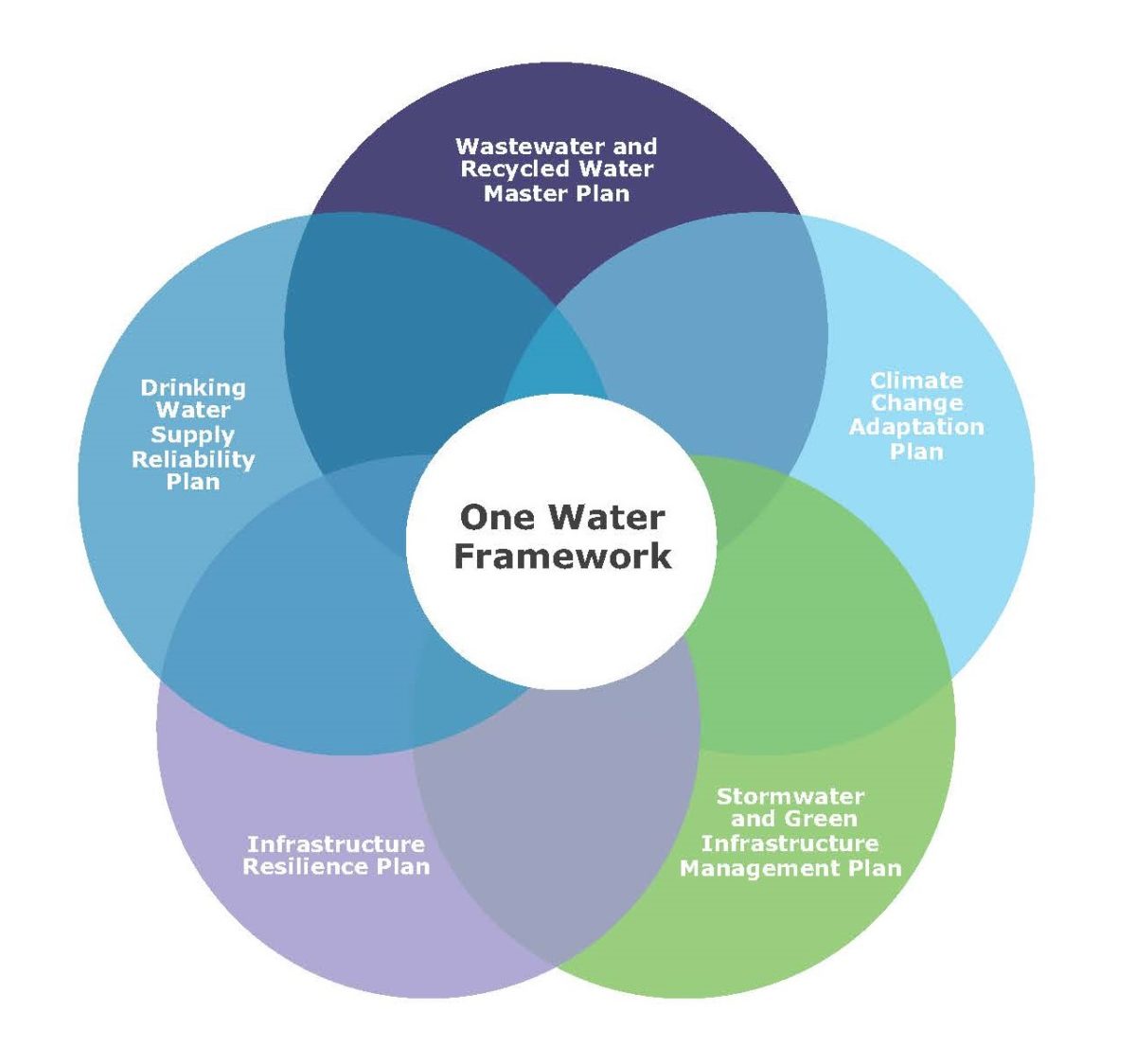

- Explore taking a One Water approach to managing water resources

Medium-Term

- Consider developing a customer assistance program to ensure affordable access to water & sewer service

- Study creating a comprehensive septic system assistance program

- Consider pursuing a grant to conduct a utility Merger/Regionalization Study

- Develop a water conservation program

- Explore creating a stormwater utility to better manage runoff and flooding

Long-Term

- Promote utility coordination on water conservation measures

- Explore creating a utility watershed protection program

- Participate in an annual water resources symposium to share the latest ideas, such as the one sponsored by the C. Water Resources Research Institute

- Develop a green infrastructure plan and promote integrated land and water management

Key Stats

- A typical town block generates nine times more stormwater runoff than a woodland area of the same size because of impervious surfaces such as roof- tops and pavement (US EPA).

- A major flooding event in the Triangle could make more than 30,000 properties in Orange, Durham, Wake, and NE Chatham Counties inaccessible to residents and emergency vehicles due to inundated roads (Triangle Regional Resilience Partnership 2018)

- Local utilities in North Carolina collectively face about $10.7 – $13.7 billion (in 2020 dollars) in water and wastewater capital projects over five years (UNC SOG Environmental Finance Center, 2021).

- The City of Raleigh expects water demand in the city and six towns its serves in eastern Wake County to nearly double to 98 million gallons a day between 2019 and 2047 (Raleigh News & Observer, 5-17-19).

Example: Claremont/Hickory Utility Regionalization[3]

In 2016, the Cities of Claremont (pop. 1,600) and Hickory, NC (pop. 40,400) conducted a Merger/Regionalization Study with a grant from the N.C. Dept. of Environmental Quality to explore the benefits of collaborating on wastewater treatment. The study found that sending sewage to Hickory would enable Claremont to tap Hickory’s staff expertise and create economies of scale that would save both communities money and reduce Claremont’s wastewater violations. They then worked with the Western Piedmont COG and the UNC Environmental Finance Center to help structure collaboration and develop sewer rates to pay for the interconnection so that Hickory could treat Claremont’s wastewater. The communities expect significant annual cost savings when the project is completed in 2024.

Click here to complete our survey about North Carolina drivers of change!

References

Environmental Finance Center, UNC School of Government. Crafting Interlocal Water and Wastewater Agreements. 2017.

_____. Evaluating Customer Assistance Programs: Orange Water and Sewer Authority. 2023.

_____. NC Stormwater Utilities Resource Hub.

_____. Online Water and Utility Resources Hub.

_____. Plan to Pay: Scenarios to Fund Your Capital Improvement Plan.

Erin Rugland. Integrating Land Use and Water Management: Planning and Practice. Policy Focus Report, Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. 2022.

Karin Rogers, Matthew Hutchins, James Fox, and Nina Flagler Hall. Triangle Regional Resilience Assessment. UNC Asheville’s National Environmental Modeling and Analysis Center for the Triangle J Council of Governments. 2018.

Rouse, David and Econsult Solutions, Inc. Financing Green Infrastructure: Lessons from the Chesapeake Bay Watershed, International City/County Management Association (ICMA). 2022.

NC Source Water Collaborative. NC Source Water Protection Award Winners.

Triangle J Council of Governments. A One Water Vision for the Jordan Lake Watershed. 2021.

U.S. Water Alliance. One Water Roadmap: The Sustainable Management of Life’s Most Essential Resource. 2016.

[1] N.C. Division of Water Resources. Water Quality Data Assessment Webpage.

[2] Federal Emergency Management Agency. National Risk Index.

[3] Environmental Finance Center, UNC School of Government. “Small Town Regionalization Case Study: City of Claremont, North Carolina.” 2021.