Social Capital as a Workforce Development Tool

At the individual level, social capital networks help all people access resources that promote economic mobility. However, low-income young adults are more likely to be disconnected from individuals and institutions that promote economic mobility through the labor force. Programs that intentionally build social networks for these young adults to such individuals and institutions may help them gain the knowledge about opportunities and skills needed that lead to career advancement.

Economic growth tends to be found in communities with strong social networks.[i] Why? The theory is that social interactions between individuals, between individuals and businesses or other community organizations, and across all organizations build trust, which results in more win-win interactions, and ultimately, better economic outcomes all around. This is the process of building and leveraging social capital—the networks that facilitate trust to improve efficiency in society.

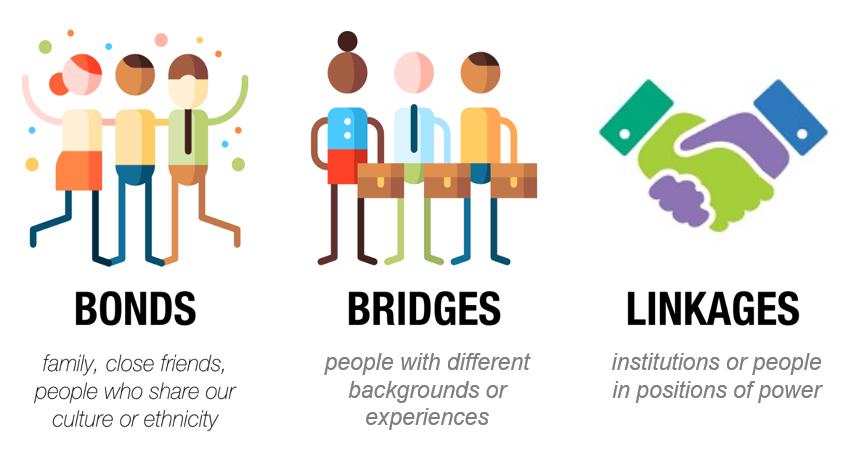

Researchers suggest social capital – relationships built on trust and reciprocity — is key for the types of development that promote faster and more sustainable economic growth.[ii] Generally, they point to three types of social capital:

- Bonding social capital refers to relationships built among individuals with similar characteristics, experiences, or group membership (“people like me”).

- Bridging social capital refers to relationships built among individuals, communities, or groups with differing background characteristics or group membership (“people different from me”).

- Linking social capital includes networks and organizations that provide connections for individuals, communities or groups across power dynamics, giving access to more resources (individuals or institutions in positions of power).[iii]

The Innovation

CommunityWorx, a local community-based nonprofit in Carrboro, North Carolina, plans to implement a social capital-based strategy in a workforce development program for emerging community leaders in the non-profit sector. The program recognized that youth and other emerging leaders within the community, especially from disadvantaged populations or situations, often lacked a connection to traditional institutions of economic mobility, including higher ed ucation. The workforce development program will build young adult leaders’ social capital to help them acquire the network, skills, and knowledge necessary to create professional networks.

ucation. The workforce development program will build young adult leaders’ social capital to help them acquire the network, skills, and knowledge necessary to create professional networks.

The ncIMPACT Initiative rarely writes about programs that have not demonstrated high impact. However, this program is so embedded in the research that it deserves to be highlighted. [NOTE: co-author Maureen Berner serves on the CommunityWorx board.] Researchers have shown that building networks in underserved populations is highly effective in producing positive economic outcomes.[i] The local networks represent social capital, and with it, greater opportunities to be successful within their own community.

More specifically, the CommunityWorx workforce development model is built on research proving the effectiveness of mentor programs. The mentor program will focus primarily build linking social capital by providing program participants with connections to individuals in positions of power. Community partners will be connected to a mentor to expand their social network in the labor force.  For example, a community partner who is interested in working on issues of affordable housing may be matched with a mentor in a management position in that subject area. This will give the community partner the opportunity to get advice and guidance from someone in their field, all while building personal relationships. Low-income young adults who are disconnected from traditional institutions appear to particularly benefit from this type of mentorship program. By broadening their social network, individuals can increase their connections to institutions that promote economic mobility.

For example, a community partner who is interested in working on issues of affordable housing may be matched with a mentor in a management position in that subject area. This will give the community partner the opportunity to get advice and guidance from someone in their field, all while building personal relationships. Low-income young adults who are disconnected from traditional institutions appear to particularly benefit from this type of mentorship program. By broadening their social network, individuals can increase their connections to institutions that promote economic mobility.

The mentoring program is not the only social capital-based strategy. Youth will take part in peer group meetings that build relationships among group members. Group participants will bring similar knowledge and experience to the group, establishing “bonding social capital”— relationships with people like me. This is expected increase community partners chances of getting a job, furthering career advancement.

The Promise

At the individual level, social capital networks help all people access resources that promote economic mobility. However, low-income young adults are more likely to be disconnected from individuals and institutions that promote economic mobility through the labor force. Programs that intentionally build social networks for these young adults to such individuals and institutions may help them gain the knowledge about opportunities and skills needed that lead to career advancement.

At the individual level, social capital networks help all people access resources that promote economic mobility. However, low-income young adults are more likely to be disconnected from individuals and institutions that promote economic mobility through the labor force. Programs that intentionally build social networks for these young adults to such individuals and institutions may help them gain the knowledge about opportunities and skills needed that lead to career advancement.

The benefits of these new networks may be used by employers, including local governments, as a workforce development tool through:

- Feeding employment information to community-based mentorship programs.

- Partnering with local nonprofits to develop and implement mentorship programs.

- Establishing a mentorship program to move low-skill employees up a career ladder

By increasing people’s social networks, we can make it easier for people to get jobs and pursue higher skill careers—creating faster economic growth for the entire community.

——-

[i] Bjørnskov, C. (2012). How Does Social Trust Affect Economic Growth? Southern Economic Journal, 78(4), 1346-1368. doi:10.4284/0038-4038-78.4.1346

[ii]Woolcock, M. (1998). Social Capital and Economic Development: Toward a Theoretical Synthesis and Policy Framework. Theory and Society, 27(2), 151-208. Retrieved January 7, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/657866

[iii] M. Berner et al. (2020).The Value of Relationships: Improving Human Services Participant Outcomes through Social Capital. Published by U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

[iv] Woolcock, M. (1998). Social Capital and Economic Development: Toward a Theoretical Synthesis and Policy Framework. Theory and Society, 27(2), 151-208. Retrieved January 7, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/657866