A Note to Human Services Programs: Four More Practices for Building Social Capital During COVID-19

As you read through the following additional social capital practices, remember there is no one-size-fits-all approach to helping participants build social capital in a human services program. Every program has a different context with different values and goals. You, the program managers and directors, know best the population you are trying to serve. That said, here are some questions and practices that might help you.

Co-Authors: Maureen Berner, UNC SOG; Phillip Graham, RTI; Justin Landwehr, RTI; Brooklyn Mills, ncIMPACT

In the first installment of this blog series, A Note to Human Services Programs: You Can Still Build Social Connections in a Time of Social Isolation, we shared the definition of social capital, insights on different types of social capital, and general principles that human service programs seeking to build social capital should consider. In the second, A Note to Human Services Agencies: Think About What Type of Social Capital You Most Need to Build Online, we shared insights on different types of social capital and general principles that human service programs seeking to build social capital should consider.

In the third installment, A Note to Human Services Programs: Three Practices for Building Social Capital During COVID-19, we focused on three questions and corresponding practices:

- How and Where Will We Connect? – Use Peer Groups with a Facilitator to Engage Participants;

- How Will This Make a Difference? – Help Participants Build Quality and Meaningful Relationships

- Is What’s Yours Mine? – Tapping into Social Capital in Organizations to Increase Participant Social Capital

As you read through the following additional social capital practices, remember there is no one-size-fits-all approach to helping participants build social capital in a human services program. Every program has a different context with different values and goals. You, the program managers and directors, know best the population you are trying to serve. That said, here are some questions and practices that might help you.

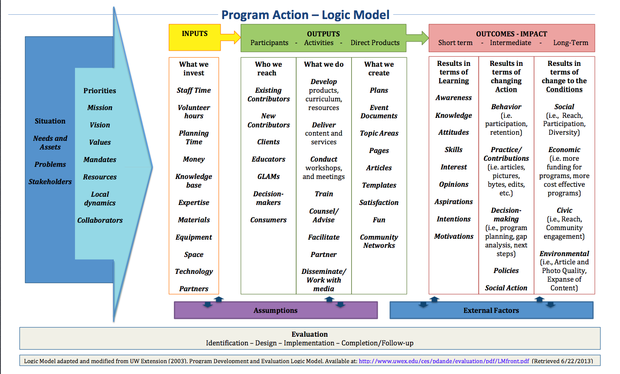

What Matters Here? – Use Data and Logic Models for Social Capital Decision-Making and Evaluation

This may be the perfect opportunity to focus on data that are key to answering questions about the importance of social capital to your program outcomes. For example, you might use a simple email or text-based survey with applications such as Survey Monkey or PollEverywhere to gather data on participants’ relationships with potential employers. This might help organizations be prepared to aid individuals to better leverage those connections for advice, training, and information about job openings during and when the pandemic is over. In another example, you might ask program participants to list their sources of bonding capital to reveal whether the connections are likely to hinder, rather than help, program outcomes, such as cases of criminal activity.

Of course, this national emergency is not the time to overly burden program participants. Many may be feeling stressed and struggling to manage all the new restrictions on everyday life. Whatever data collection you do should be easy to complete and the value must be clear to program participants.

Finally, this may be a good time for a virtual team meeting among staff to stress test the organization’s logic model. Logic models are a type of map that outline, in step-by-step fashion, how programs progress from resources and activities to short- and long-term outcomes. Does yours stand up to your aspirations for building and leveraging participants’ social capital in times such as this? This may be a time to engage your staff and a few participants in a virtual conversation supported by tools such as Zoom and Google Docs.

What About My Interests? – Create Space and Opportunity for Organic Connections to Happen

Many successful programs balance freedom and structure in creating space and opportunities for connections to develop into trusting relationships. The right physical, social, and emotional environment can help people develop relationships by creating a welcoming atmosphere, or providing spaces suitable for conversations. In-person meetings often benefit from tactics such as offering food for participants. In a virtual environment, the tactics should be more geared to interaction. Games, visual images, and a welcoming facilitator can be important to building and maintaining relationships with program participants that allow them to move from formal engagement to organic connections. Video-based platforms could be key tools in creating spaces for participants to engage remotely.

Who Came Before Me? – Include Qualified Individuals or Alumni in Programming and Staffing

The intentional hiring of former participants, or individuals with similar experiences, may add to your program’s credibility in the eyes of current participants. This can help them establish trusting relationships with staff who have a familiar background (bonding capital) and reduce the reluctance to use relationships with those who are different (bridging and linking capital) for their own personal growth. In effectively reaching out virtually to current participants, these alumni can quickly become role models because they can relate to participants and are concrete models of success.

Not all alumni will be qualified to work in a program, but when qualified, alumni may add significant value. If you don’t have alumni involved right now, you might engage some as volunteers or interns if you are able to do phone or online training. Then, they gain valuable skills and training while you are determining whether they would be a good fit as a staff member. In a note of caution, however, directors and managers may want to balance the value of these individuals with other staff who may have more diverse experiences and expertise needed by the organization during the pandemic.

How Do We Hold Each Other Responsible? – Emphasize Accountability

Accountability is one key aspect of social capital relationships. Social capital grows more efficiently when people hold each other “to their word,” and you may be worried that you are losing that spirit of accountability while so many program participants are isolated. If you don’t have a formal accountability instrument, you may want to think about the potential benefits of agreements or commitments in which participants, peers, staff, and/or supporters are explicit about what is expected of each other during the pandemic, and there is a mechanism to check back in or show fulfillment of promises online. If you already have an instrument in place, this is the time to remind participants of it. These instruments can help bring transparency, consistency, and predictability, and add longevity to the relationships with/among participants.

There are different ways to structure accountability agreements. One way is through accountability agreements among the entire group. Another is through informal agreements that hold two peers accountable to each other.

Individual social capital may also be built through accountability structures between people in a bridging social capital relationship. One of the easiest examples to understand is the relationship between a mentor and mentee. Mentorship relationships imply responsibility to communicate, connect, and respect alternative views. There is an expectation that advice is sought and provided.

Listen to the Podcast

The COVID-19 pandemic is causing people around the world to question how this virus will affect the many public and private systems that we all use. Click here to hear more thoughts from a podcast about Social Capital from ncIMPACT’S director, Anita Brown-Graham, as part of a series of Viewpoints on Resilient & Equitable Responses to the Pandemic from UNC’s Center for Urban and Regional Studies.

The material for this blog series has been adapted from content based on: information gathered by engaging a panel of national experts for interviews and focus groups; conducting a national program scan of notable human services programs using social capital; visiting agencies in person, and writing in-depth case studies with selected programs, and augmented by research on virtual communities conducted by Anita Brown-Graham. The team responsible for that original content includes The Office of the Assistant Secretary to Planning and Evaluation at the United States Department of Health and Human Services, RTI International, and the ncIMPACT Initiative at the School of Government at UNC-Chapel Hill. All images are stock photos. This does not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Health and Human Services. Nothing in this blog series should be construed as endorsing any company or platform.

[1] Woolcock, M., & Narayan, D. (2000). Social Capital: Implications for Development Theory, Research, and Policy. The World Bank Research Observer 15(2) 225–249. https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/15.2.225

[1] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, https://www.hhs.gov/ash/oah/resources-and-training/tpp-and-paf-resources/cultural-competence/index.htm –

[1] Mayer, J. D., Roberts, R. D., & Barsade, S. G. (2008). Human abilities: Emotional intelligence. Annual. Rev. Psychol., 59, 507-536.

3 Responses to “A Note to Human Services Programs: Four More Practices for Building Social Capital During COVID-19”

A Note to Human Service Agencies: Think About What Type of Social Capital You Most Need to Build Online - Facts that Matter

[…] A Note to Human Service Programs: Three Practices for Building Social Capital During COVID-19, and A Note to Human Service Programs: Three Practices for Building Social Connections in a Time of Socia…, to serve those clients who have access to the phone and virtual […]

A Note to Human Service Programs: You Can Still Build Social Connections in a Time of Social Isolation - Facts that Matter

[…] the fourth installment, A Note to Human Service Programs: Three Practices for Building Social Connections in a Time of Socia…, offers additional practical tools and frameworks for […]

A Note to Human Service Programs: Three Practices for Building Social Capital During COVID-19 - Facts that Matter

[…] are the first three practices. [NOTE: Blog Four in this series, A Note to Human Service Programs: Three Practices for Building Social Connections in a Time of Socia…, covers four more […]